Learning the secret language of electronics might sound like a superpower, but it's really about Understanding Circuit Schematics. These intricate diagrams are the blueprints, maps, and instruction manuals for everything from a simple LED blinker to the complex circuitry inside your smartphone. Master them, and you unlock the ability to design, build, troubleshoot, and truly understand the devices that power our world.

You're about to demystify those cryptic lines and symbols, transforming them from a jumble of abstract art into clear, actionable intelligence.

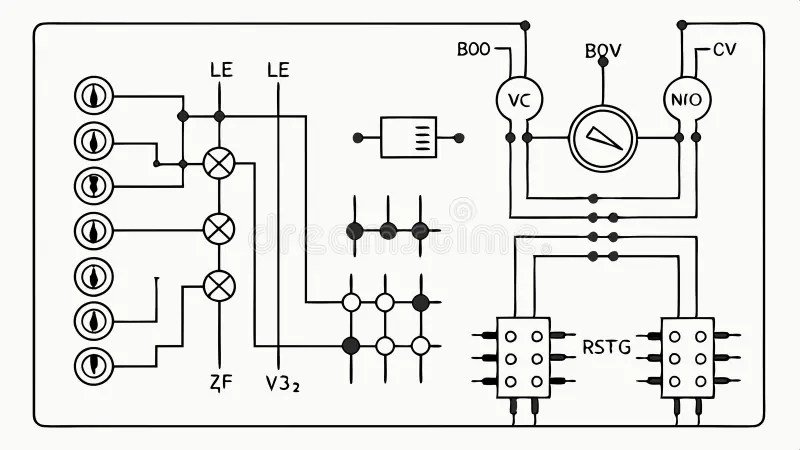

At a Glance: Decoding Circuit Schematics

- Schematics are roadmaps: They show how electronic components connect to form a working circuit.

- Symbols are the vocabulary: Each standardized graphic represents a specific component (resistor, capacitor, transistor, etc.).

- Lines are the highways: They indicate electrical connections and current paths.

- Labels provide context: Values, part numbers, and net names offer critical information.

- Reading direction matters: Generally left-to-right, top-to-bottom, like a book.

- Troubleshooting power: Schematics guide you to pinpoint issues by revealing expected behavior.

- Practice is key: Start simple, learn common patterns, and build your confidence over time.

Why Every Electronically Curious Mind Needs This Skill

Imagine trying to build a house without architectural drawings, or assembling flat-pack furniture without the instruction sheet. That's essentially what working with electronics without schematics feels like. These diagrams aren't just for electrical engineers; they're indispensable for anyone who wants to:

- Build a project: From hobby kits to custom designs, a schematic ensures you connect components correctly.

- Repair a device: Quickly identify faulty parts and understand how they interact with the rest of the circuit.

- Modify an existing design: See exactly where to tap into a signal or inject power without causing damage.

- Design your own circuits: Translate your ideas from concept to a tangible, buildable plan.

Think of a schematic as the DNA of an electronic device – it contains all the genetic information needed to replicate and understand its function. Ready to dive deeper? You can always Explore the Schematically hub for more foundational knowledge.

The Foundation: What Makes Up a Schematic?

Every schematic, no matter how complex, is built from a few fundamental elements. Once you grasp these, you're well on your way to fluency.

1. The Symbolic Language of Components

This is the core vocabulary. Each electronic component has a unique, standardized symbol. These symbols are universally recognized, meaning a resistor symbol looks the same in a schematic from Tokyo as it does from Toronto.

Think of symbols as shorthand for physical components. Here are a few examples:

- Resistors: Zig-zag lines or a rectangle. They oppose current flow.

- Capacitors: Two parallel lines, sometimes one curved. They store electrical charge.

- Diodes: A triangle pointing at a line. They allow current in one direction only.

- Transistors: A circle with three leads and internal arrows. They amplify or switch signals.

- Power Sources: A circle with +/- or parallel lines of varying lengths for batteries.

We'll dive into a more comprehensive list of common symbols shortly, but the takeaway here is: learn your symbols. They are the building blocks of understanding.

2. Lines, Nodes, and Connections

Just as words are connected by sentences, components in a schematic are connected by lines.

- Lines (Wires): These straight lines represent electrical conductors, or wires, carrying current between components.

- Nodes (Junctions): When two or more lines (wires) connect, it's typically indicated by a small dot at their intersection. This dot signifies an electrical connection. If lines cross without a dot, they are NOT connected – think of it like an overpass on a highway. Sometimes, a "jump" or semi-circle over the crossing line is used, but the absence of a dot is the most common indicator of no connection.

3. Labels and Annotations: The Context

Symbols tell you what a component is, but labels tell you more about it.

- Reference Designators: Every component usually has a unique alphanumeric label. For instance,

R1for the first resistor,C2for the second capacitor,U3for the third integrated circuit. This allows you to refer to specific parts in a bill of materials or during troubleshooting. - Component Values: These specify the component's electrical properties. A resistor might be labeled

10kΩ(10 kilo-ohms), a capacitor0.1µF(0.1 microfarads), or an inductor100µH(100 microhenries). Universal recognition of SI units like ohms, farads, and henrys is crucial here. - Part Numbers: Sometimes a specific manufacturer's part number (e.g.,

2N2222for a transistor) is included, especially for unique or critical components. - Operational Notes: Short descriptions might clarify a circuit's function or a component's role, like "Input Signal" or "LED Indicator."

4. Power and Ground: The Circuit's Lifeblood

No circuit runs without power. Schematics clearly show where power enters and exits the circuit, and where the common return path (ground) is.

- Power Symbols: Often denoted by

VCC,VDD,V+, or+5V, these symbols show the voltage supply points. - Ground Symbols: These are often represented by a series of horizontal lines decreasing in length, or a triangular symbol. Ground is the common return path for current and typically represents the circuit's negative reference point.

5. Polarity: Direction Matters

For many components, the direction they're installed matters. This is called polarity.

- Polarized Capacitors: These have a positive and negative terminal that must be connected correctly. The schematic symbol will usually show this, often with a

+sign or one plate being curved. - Diodes and LEDs: These only allow current to flow in one direction. The symbol (a triangle pointing at a line) indicates the direction of forward current (the arrow points from positive to negative, often referred to as anode to cathode).

- Transistors: Have specific emitter, base, and collector (or source, gate, drain) connections that are polar.

- Batteries: Always have a positive (longer line) and negative (shorter line) terminal.

Connecting a polarized component backward can prevent the circuit from working, or worse, destroy the component. Always pay attention to polarity!

Navigating the Blueprint: How to Read a Schematic Like a Pro

Understanding the individual elements is one thing; putting them together to comprehend the entire circuit's operation is another. Here's a systematic approach.

1. Understand Basic Electrical Concepts

Before you can read the "sentences" of a schematic, you need to understand the "grammar." This includes:

- Ohm's Law (V = IR): This fundamental law describes the relationship between voltage (V), current (I), and resistance (R). It's crucial for understanding how components affect each other.

- Series and Parallel Circuits: How components behave when connected one after another (series) versus side-by-side (parallel). Knowing how resistance, capacitance, and inductance combine in these arrangements is foundational.

- Component Working Principles: Expertise to interpret symbols accurately. For instance, knowing capacitors are used for decoupling, bypassing, or blocking DC is key to understanding their role.

2. Follow the Flow: Left-to-Right, Top-to-Bottom

Most schematics are organized logically, much like a book.

- Input to Output: Typically, the signal or power enters from the left and progresses towards the right, where the output is.

- Power Rails: Power supplies (VCC, VDD) are often shown at the top, with ground (GND) at the bottom.

- Functional Blocks: The circuit might be visually segmented into functional blocks (e.g., power supply section, input stage, processing stage, output driver).

By tracing the path of current or signal, you can understand how the circuit transforms the input into the desired output.

3. Segmenting Complex Circuits: Divide and Conquer

Large schematics can be overwhelming. Don't try to understand everything at once.

- Identify Functional Blocks: Look for natural groupings of components that perform a specific task (e.g., a power regulation section, an amplifier stage, a micro-controller section). These are often clearly delineated or implied by their arrangement. Block diagrams are excellent for illustrating these functional connections without internal details.

- Net Labels: Instead of drawing long, messy wires across the entire schematic, designers use "net labels." These are names (e.g.,

VIN,AUDIO_OUT,RESET_N) attached to specific electrical connections. If two points have the same net label, they are electrically connected, even if no visible wire connects them. This significantly cleans up complex designs. For example, a 3.7V lithium-ion battery charger might have distinct sections for input, main IC, charge control, and output, connected by net labels likeCHARGE_CTRL_V.

4. Leverage Practical Tools

Reading a schematic isn't just a theoretical exercise. It's often paired with hands-on work.

- Component Datasheets: When you encounter a specific IC or transistor, its datasheet provides detailed information about its pins, functions, and typical applications. This is invaluable for understanding how a component works within the larger circuit.

- Multimeters: Use a multimeter to verify voltages, currents, and resistances at various points in the physical circuit, comparing them to the expected values derived from the schematic. This is the cornerstone of effective troubleshooting.

Decoding Common Schematic Symbols: Your Visual Dictionary

Here's a deeper dive into the most common schematic symbols you'll encounter, along with a brief explanation of their function.

Power Sources

- DC Power Source: A circle with

+and-inside, or a line of varying lengths. Provides current in a constant direction. - AC Power Source: A circle with a sine wave inside. Provides current that oscillates in two directions.

- Battery: A series of long and short parallel lines. The longer line is the positive terminal.

- Ground: A series of horizontal lines decreasing in length, or a triangle symbol. The common return path.

Terminals & Connectors

- Terminal: An empty circle. A connection point to an external circuit or component.

- Header/Connector: Often represented by a row of pins.

Switches

Switches make or break connections, or change current paths.

- SPST (Single-Pole Single-Throw): Basic on/off switch.

- SPDT (Single-Pole Double-Throw): Connects one input to one of two outputs.

- Momentary Switch: Only active while pressed (e.g., a push button).

Passive Components (They Don't Generate Power)

- Resistor: Zig-zag line or a simple rectangle. Opposes current flow, dissipating energy as heat. Labels:

R1,10kΩ. - Variable Resistor (Potentiometer): Resistor with an arrow through it or a third lead. Resistance can be manually changed.

- Photoresistor (LDR): Resistor in a circle with incoming arrows. Resistance changes with light intensity.

- Capacitor: Two parallel lines (non-polarized) or one curved line/plus sign (polarized). Stores electrical charge. Labels:

C1,0.1µF. - Inductor: A coiled line. Stores energy in a magnetic field. Labels:

L1,100µH. - Transformer: Two coils separated by lines (iron core). Steps up or down AC voltages.

Active Components (They Can Amplify or Switch Signals)

- Diode: Triangle pointing towards a line. Allows current in one direction only (anode to cathode).

- LED (Light Emitting Diode): Diode symbol with two arrows pointing away. Emits light when current flows.

- Zener Diode: Diode with bent ends on the line. Allows current in reverse direction above a certain breakdown voltage.

- Transistor (BJT - Bipolar Junction Transistor): A circle with three leads (Base, Collector, Emitter) and an internal arrow. Amplifies or switches signals.

- NPN: Arrow on emitter points outward.

- PNP: Arrow on emitter points inward.

- Transistor (MOSFET - Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor): Similar to BJT but with Gate, Drain, Source leads. Often used as switches.

- Relay: A coil symbol (inductor) connected to a switch symbol. Electrically operated switch.

- Integrated Circuits (ICs): Represented by a rectangle with pins. These perform complex functions.

- Operational Amplifiers (Op-amps): Triangle symbol with five leads (two inputs, one output, power). Voltage amplifiers, e.g.,

LM358. - Logic Gates: Symbols represent boolean functions:

- AND Gate: D-shaped. Output is true only if all inputs are true.

- OR Gate: Curved D-shape. Output is true if at least one input is true.

- NOT Gate (Inverter): Triangle with a circle at the output. Output is the opposite of the input.

- XOR Gate: Curved D-shape with an extra curved line at input. Output true if inputs are different.

- NAND, NOR, XNOR: Similar to AND/OR/XOR but with a circle at the output indicating inversion.

- Microcontrollers, Voltage Regulators: Often shown as a large rectangle with many labeled pins.

Optoelectronic Devices

- Photodiode/Phototransistor: Diode/Transistor symbol with incoming arrows. Light-sensing.

- Solar Cell: Battery symbol with incoming arrows. Generates electricity from light.

Other Common Symbols

- Speaker: A horn-like symbol. Converts electrical signals to sound.

- Microphone: A circle with lines, often resembling a diaphragm. Converts sound to electrical signals.

- Fuse: A curved line or a box with a line. Protects circuits from overcurrent.

- Motor: A circle with 'M' inside. Converts electrical energy to mechanical motion.

- Antenna: A 'T' or zig-zag line. Transmits or receives radio waves.

Crafting Clear Designs: Principles of Professional Schematic Design

While you're primarily reading schematics, understanding good design practices will make interpreting them much easier. Professional schematics are an art form in themselves.

- Logical Wiring & Organization: Components are grouped logically, and wires run as straight as possible, minimizing crossovers. Power and ground lines are often distinct.

- Appropriate Labels: Every significant component and connection point is clearly labeled with its reference designator, value, and (if helpful) a net name.

- Terminations: Connections are always clearly indicated with dots (nodes). Unconnected crossings should be unambiguous.

- Color-Coding (Optional): In software, designers sometimes use colors to represent different attributes, like red for power, black for ground, and various colors for different signal paths. This isn't part of the standard, but it can enhance readability.

The Ultimate Power: Troubleshooting with Schematics

This is where the true value of schematic understanding shines. A schematic isn't just a guide; it's your most powerful diagnostic tool.

1. Isolate the Problematic Section

If a circuit isn't working, don't randomly probe. Use the schematic to identify the functional blocks. Is the power supply working? Is the input signal present? By isolating the faulty section, you narrow down your search considerably. For instance, in that battery charger example, if the output isn't supplying current, you might first check the charge control section (inductor, capacitor, diode for buck conversion) before looking at the input or battery selection.

2. Check Connections and Component Integrity

The schematic tells you exactly how everything should be connected.

- Continuity: Use your multimeter to check for continuity between connection points that should be linked according to the schematic.

- Opens/Shorts: Check for wires that are broken (open circuit) or accidentally connected where they shouldn't be (short circuit).

- Faulty Components: The schematic helps you locate specific components (e.g.,

R10_CC_CTRLwhich sets max current) that might be failing, especially if their values are critical.

3. Understand Expected Voltage and Current Values

A good schematic, or accompanying documentation, might list expected voltage levels at key test points.

- Diagnosis: Use your multimeter to measure actual voltages and currents and compare them to the schematic's implied or explicit values. If a voltage is unexpectedly high or low, or current isn't flowing where it should, the schematic helps you trace back to the source of the anomaly. Ohm's Law becomes your best friend here, allowing you to calculate expected current or voltage drops across resistors.

Building Your Schematic Muscle: Next Steps and Practice

Like learning any new language, fluency in schematics comes with practice and exposure.

- Memorize Common Symbols: Start with the most frequently used components (resistors, capacitors, diodes, power, ground). Use flashcards or online quizzes.

- Practice on Simple Circuits: Find schematics for basic projects (e.g., an LED flasher, a simple amplifier, a voltage divider). Try to draw the physical circuit based on the schematic, or vice-versa.

- Experiment and Build: The best way to learn is by doing. Build a simple circuit from a schematic, and then try to troubleshoot it if it doesn't work. The practical application solidifies theoretical understanding.

- Explore Online Resources and Tutorials: Websites, forums, and YouTube channels offer countless examples and explanations. Don't be afraid to read multiple perspectives.

- Examine Existing Devices: If you have an old, broken electronic device, try to find its schematic online and trace the connections. This gives you insight into real-world design.

Your Electrical Journey Starts Here

Understanding Circuit Schematics is more than just a technical skill; it's a gateway. It transforms opaque black boxes into transparent systems, allowing you to participate actively in the world of electronics, rather than just being a passive consumer. With every symbol you recognize and every current path you trace, you build confidence, expand your capabilities, and unlock new possibilities for innovation and repair. So grab a simple schematic, a pencil, and start tracing. The world of electronics is waiting for you to read its story.